Jake Yarris

Forum Replies Created

-

AuthorPosts

-

Jake YarrisParticipant

Jake YarrisParticipantCheryl, it’s great to hear your reflections, and you did a great job instructing! Kind of you to say I was doing a ‘good job’, since I had no idea how mine came out, and I was thinking that you did a good job! I really liked how you outlined the principles of mindfulness of body and mindfulness of mind in your instruction and here in your reflection. This was a learning point that I will take from you! 🙂

Jake YarrisParticipant

Jake YarrisParticipantJoe, it’s great to hear that you weren’t nervous or uncertain. I can relate to your reflections on posture– I had a recent experience just before this class with receiving a full instruction and realizing that my posture and attention to posture had become a little lax, and that posture cues were really helpful to my practice. Preparing the body opens the mind.

Jake YarrisParticipant

Jake YarrisParticipantI would say it was exciting to offer instruction. I was nervous, and I felt my voice and mind both wavering a bit. I tried to take a deep breath, and continue instruction. I tried to rest in the feeling of my own meditation, and give instruction based on that. I am enjoying the exploration of the interplay between the giving of instruction, and the receiving of your own instruction, and the practice, which the teacher and the students are all doing together. I was happy for the opportunity to teach another and grateful for my partner for receiving my instruction. I was a little uncertain about my delivery, but I did trust in my own practice and ability to teach. I do feel trust in myself in this process.

Jake YarrisParticipant

Jake YarrisParticipantGlenn, your story is fascinating and thank you for sharing! In your story I can reflect this curious sense that we seem to experience, where meaningful things can seem to happen from almost chance occurrences, or that a strong connection may arise to something and we cannot determine the source. There is an intertwining between what we are born into and what we aren’t born into, what we chose and what we don’t chose. It’s up to each of us to walk those paths, and make our own reflections and wisdom, and those wisdoms become true because we experience them.

Jake YarrisParticipant

Jake YarrisParticipantOctavio, thank you for sharing, and for your honesty. I was fascinated by your description of lineage and your continued search for home in that sense. I wish you luck and keep exploring! These are concepts which in many ways must be defined and explored by each of us individually and there aren’t right or wrong answers.

Jake YarrisParticipant

Jake YarrisParticipantI suppose I think of lineage as the people who have made a large enough impact on my life that I feel I am carrying some of them or something about them forward with me. I believe lineage is passed through time and care, love and inspiration, and you know when someone joins that group. Many people give you something valuable or inspire you but they don’t quite join that group.

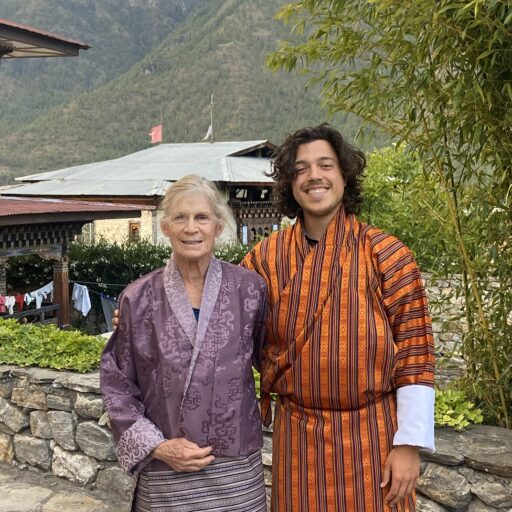

My family is my lineage–how they behave as a family, what values they expressed to me, the genes and personality traits they passed down to me. For example, these include the values of prioritizing physical health via exercise and mental health via activities which engage the brain’s learning. This also includes my ancestry – Lebanese, Polish, Irish, and to lesser extent a smattering of other European ancestries, like other white Americans who are the descendants of immigrants. I made Lebanese food with my grandparents and cousins–grapeleave, fatayer, mjudra. Aside from this, I would say generally my lineage of family relates more to behavioral and interpersonal aspects, rather than cultural, ethnic, or national.

There are certain mentors who I feel have passed to me some of their essence, beliefs, traits, or skills–my longtime guitar instructor and dear friend, Jamie Stillway, a few kind teachers from my martial arts school, my swim coach, two of my previous bosses perhaps. I have been touched by and spent time with a few different Buddhist teachers, though I would not say I have a guru teacher. Or maybe I do but I’m not aware of it… it can be a mysterious process. In Buddhist terms I have been exposed to both the Nyingma and Kagyu lineages, though again, I’m not sure I have a direct guru at this time. Jake YarrisParticipant

Jake YarrisParticipant-note, I’m glad this is our essay question this week, since there seemed to be a lot of interesting stories in the class period and I’m curious to hear what you all have to say!

Nihilism, meaning that there is other determined purpose for your life, that nothing follows death, that without established meaning no actions or behaviors actually matter. What follows is that each individual determines their own meaning and purpose, and essentially their own rules or lack thereof for existence. My sense of relating to this philosophy comes from a non-religious upbringing. I was not taught about God, and only in a sort of socio-culturally accepted sense did I understand heaven. People said that after you die you go to this other, better place, where you can see your dead relatives. As a child this made enough sense to me–though it was vague and unexplained, it seemed fair. Also, I understood that anyone went there, including pets and animals. This was my child-like eternalism, though it didn’t last long.

I would say that growing up into my education, the founding beliefs of that education were scientific in nature. Meaning that the mechanisms and forces of the universe come only from scientific and mathematical explanations, and unexplained phenomena could be yet explained, and explained phenomena could yet be disproven. As we explored, this can be essentially nihilistic. It doesn’t really accept faith (eternalistic or otherwise) as a valid explanation for phenomena or philosophy. I was taught to believe in scientific explanations, and I didn’t reject that viewpoint. I internalized the belief that basically once you’re dead, you’re dead. There are no gods. The scientific processes continue, cause and effect, like karma (I say with hindsight, I was not Buddhist yet). Humans make their own beliefs, some are beneficial to us, and some are harmful. I learned of many examples where it seemed people formed religious beliefs around selfish goals and which resulted in violence and injustice. I actually developed a resistance to organized religion based on my educational environment and my sociocultural setting.

However, since I was very young, I have felt attuned to the particular, nonverbal, felt tone of experiences and places and emotions. In an essentially “non-scientific” way. This was especially noticed in my experiences of nature and art and books. It was related to my artistic sensibilities, and my introspective personality as well. And yes, I am a 4.

In high school I found God. Or at least, I thought I did. I just didn’t see it the way I used to, as a made-up bearded man in the sky, who I couldn’t relate to at all. I began to have feelings of a deep and secret beauty, permeating all things. I believed that all things were connected, which was actually supported by my scientific understanding of the universe. I imagined a flow of energy and matter like a constant river through the night sky. A river we are all a part of and can remember at any time. This was my God. It was the love of the Universe. All matter is interconnected and interactive, and is changed into different forms of itself, and is never created or destroyed. In the same way I felt that Love and beauty permeates us all, connects us, and when we die, our matter and our “souls” (whatever that is), returns to the One.

This is my personal example of science NOT being nihilist, but rather eternalist. And if you look at history you in fact see many scientists who believe in God, and their belief is affirmed rather than denied by their study of science and mathematics.

Anyway, I started listening to podcasts of Sufi wisdom by the professor Omid Safi. I fell in love with the teachings, the poetry, and the man himself. I fancied myself becoming a mystic Muslim. I listened to Quran recitations, found the copy in our house, and wanted to learn Arabic. I got books by Rumi and Hafez. I also agreed with Dr. Safi, who said that all the mystics of many traditions, the truest wisdom of all creeds, converged on this same wisdom of ever-permeating and flowing Love, which he calls the Islamic God, Allah, but many can and do experience under different names and descriptions. I agreed that it seemed that many mystics of different backgrounds, at some point through their seeking, often came to the same wise and revealing conclusions about connectedness and love in our existence.

At a similar timeline I started meditating and being exposed to Vajrayana Buddhism. This wasn’t contradictory but rather developed alongside other beliefs, practices, and wisdom, in conversation with each other. In college I continued to have spiritual experiences, unexplained and mystic feelings. I swam through the ocean and sang on the cliffs under night stars. I played improvisational music with friends by firelight. I hiked and camped far and wide under different wildernesses but the same sky. At times I felt God with me, or rather remembered that interconnected love which I would say is the God I know, and at other times I wasn’t sure if I related to the concept of a god.

Meanwhile my Buddhist practice and study developed. I felt more and more that these were teachings I had known and held within me all my life, and that they were slowly permeating and opening my life.

Today, I have taken refuge within this path. I never did become a Muslim, though I suppose that could still happen. As a mystic Buddhist, I still carry that openness for experiences beyond description, for the unexplained, for even the divine. I know I can’t pretend to explain or understand it in full, so I don’t try to. Any religion could be “right”, but that isn’t really important to me. I live through my lived experience and practice and if anything choose to believe in intrinsic goodness, beauty, and interconnectedness, because why would you want anything else to be true? As well as my experience seems to reflect this. The practices and teachings of Buddhism have been greatly influential to me, and beneficial to myself and others. In this way I suppose I had a personal development of the “middle way” between eternalism and nihilism.

Jake YarrisParticipant

Jake YarrisParticipantOctavio, really well said.

Yes, I agree with you in the feeling that the answer is inside all of us. Or that, we all contain the right answers. There is some sense that we don’t have to get them from somewhere else.

Yes, comfort with uncertainty. Comfort with uncertainty, and comfort with DIScomfort, to me comprise such a core benefit and practice of meditation. Learning to sit with uncertainty and discomfort sounds terrible, but when we realize that our days are chock full of these things, then becoming more accepting of the experiences of our lives makes them more meaningful (and enjoyable!). Easier said than done of course. But once we realize that our lives are an uncertain, ungrounded mess, than we can actually start to work with that situation, rather than tumbling through some kind of painful denial of that truth.

Octavio, thank you for sharing, and I’m so glad you decided to join the Meditation Teacher Training course! It’s my personal opinion that you are a great candidate 🙂

I can also echo the experience of being drawn to meditation and Buddhism for no discernible reason, some indefinable draw to the teachings. It’s interesting that this happens to us and I have heard a similar reflection from many practitioners. The teachings seem to come to us, draw to us, rather than the other way around. Jake YarrisParticipant

Jake YarrisParticipantDear Glenn,

Thank you for sharing. I love your image of the explorer and the landscape, and how we as explorers can travel to the landscapes of others, with open minds and hearts, and finding common ground between our experiences in the goal of mutual understanding and aid. And I really appreciate how you explore the concept of how we are balancing this Buddhist (at least, to me it appears in Buddhism) coexistence of both the embracing of the newness of an experience, without attaching prior judgements or opinions, while also being supported by this very old and tested lineage of discovery and investigation. I hope you find these benefits in this course as you describe! Jake YarrisParticipant

Jake YarrisParticipantDear Anita,

Wow, this is such a beautiful reflection on the container and it really spoke to me. Thank you for sharing! You outline the power, versatility, and close-heartedness of the container in such a compelling way. I like how you highlighted the importance of a teacher to stay true to your practice and to practice what we are teaching. By our own deepening of our practice we can understand what jewels we have to offer others. And through our own learning we may discover endlessly helpful tools to assist others. I can’t tell you how many times I have been in a meditation class and a fellow student has offered a brief reflection or metaphor which has been of tremendous benefit to the learning and practice of that sangha. Thanks again for your essay! Jake YarrisParticipant

Jake YarrisParticipantI think the first priority is safety. Meaning that with a student, peer, friend, or loved one, we must do what is in our power to create a safe environment for the discovery to begin. If there are circumstances with the situation and the student which could lead to unsafe or traumatic experiences, and if we are not specifically able to support or assist in those situations, we might recognize that we are not able to engage in discovery until those needs are met with the help of other resources. Once safety is established, discovery can begin. As Susan mentioned in the first class, when we are meditation teachers, we are not doctors or therapists. Unless you are actually both, of course. In fact, I do know one of such people personally. In which case I still imagine it would be difficult or even inappropriate to be a doctor and a meditation teacher at the same time.

Next, listening is paramount. Supporting discovery means allowing the student to guide the experience. We leave our personal thoughts and feelings momentarily aside while we engage with the thoughts and feelings of another. We do not tell the student what to say, what to do with their experience. It is important to simultaneously engage deeply with this spiritual friend and, as being in a teacher position, maintain an appropriate distance. We should not immediately impart our opinions and reactions as we are used to doing in everyday life. We are able to offer the established and tested wisdom of the practice as a template. In addition, the teachings say that if we stay with what is, the meaningful action or response will arise, from a communication between the situation as it is and our basic goodness, our buddhanature.

We should not pass judgements, criticisms, or corrections on what the student authentically experiences and shares with us or others. As teachers it is important for us to make each student know that their personal experience and reaction to the teachings and practice is important and valid. We are all human, and our experiences of life and the dharma are as myriad as they can be mirrored. A relevant teaching, anecdote, or response may arise in our mind which we can impart if it is appropriate to this teaching environment. Or nothing may arise in our mind in response. There is no right answer and this is often the best answer. We can always thank our students for sharing, because each sharing is an opportunity for ourselves as teachers and any students–including the sharer—to learn. We can also reassure the student that their experience is important and valid, and they aren’t doing anything wrong by having that experience or sharing it.

If we are teachers, why shouldn’t we tell our students what to do? Aren’t we supposed to have the tools, knowledge, and wisdom to guide and create discovery? Not really. We aren’t teaching geometry or physics. The best justification for this approach may be this: for each person, each student of the dharma which we all are, even if we are teachers, THAT person is the only one who can walk the path and discover it for themselves. We can’t walk the path for them. And this is a beautiful truth of our lives, so let’s embrace it!

Jake YarrisParticipant

Jake YarrisParticipantI had some surprises when confronting the five buddha families. I believe Susan and I share the same enneagram type, 4, and further, 4 (self preservation), and understanding some of the characteristics of this type would leave me to expect to find myself drawn to Padma and secondarily Karma, as I think Susan used as an example in class. But that in reality, that is not what drew me…

Again, I really like the explanation of the enneagram and of the buddha families as that everyone can experience and embody each energy, fluctuating and flowing, and though they may represent “home bases” for some, learning about these energies as a whole gives us an interesting array of tools to interact with and understand the world and each other. Expecting myself to be drawn to Padma, I instead felt a very strong pull to Ratna. This made me curious because it seemed that few others in the class were drawn to Ratna… perhaps being turned off by appearances of being “messy” or “materialistic”, seemingly anti-buddhist concepts, familiar with negative emotions associated with our heavily consumerist and materialist society. But I immediately resonated with the aspect of Ratna recognizing the incredible richness in everything that surrounds us, in every mundane moment. A large part of my spiritual journey (winding, bringing me eventually here to Tibetan buddhism) has been an exploration of the two connected feelings of a) the profound interconnectivity (emptiness) of phenomena, reality, beings, etc and b) the incredible richness to be found within each waking moment. The falsity of looking for “richness” in some other place, or some other time, or some other material circumstance, and the truth of the incredible richness in each moment, so rich that we cannot absorb, comprehend, or even realize it all. I feel Ratna in the summer afternoons sent sitting in my small backyard (messy, old, used) next to a crumbling treehouse, the coos of chickens, nearby highway sounds, ripening blueberries, a mishmash of grass and concrete and paved stones in a haphazard wall. I immediately felt Ratna during class, sitting next to my bedside table (which is my guitar amplifier) surrounded by candles and a tangle of guitar cords and stacked up books and clothes I should put away and my meditation cushion and tossed around pillows and my mala beads and plants and art notebooks and posters and paintings and pictures on the walls.

So I feel a sense of pride with this discovery of the Ratna family: the family of messy gardens in the afternoon, of an artist’s insanely cluttered studio, of a notebook filled with doodles and drawings and quick-written poems and taped-in plant parts and to-do lists and score tallies from card games. Jake YarrisParticipant

Jake YarrisParticipantI have been practicing the heart sutra before almost every meditation, after making offerings and requesting blessings, and considering my recitation of the sutra to be one of my offerings. I recite in an even rhythm, and something I learned from practicing with a group rather than alone is that when I need to breathe in, I continue reading even as the correct sounds are not made, and pick up after the in-breath. This, to me, grants a little bit of a better flow, and a sense that once in motion, the sutra is continuing on its own even as I physically have to take breaths.

The sutra seems to add a sense of clarity, “calmness”, and profoundness, and knowledge, always feeling like something I approached, and it passed by me, and left me with something in my pocket, and the feeling like something profound and true rippled by… After my morning meditations I make breakfast and go to work. At work, when I am doing some tasks, I try to recite parts of the sutra, as much as I can remember from my mind, in the effort of getting to memorize it. Jake YarrisParticipant

Jake YarrisParticipantThe paramita I have been resonating with recently is “exertion”. I have been having a lot of experiences with the buddhist nature of exertion and it was invigorating to (re)learn the paramitas and remember that exertion is a transcendent action. It has been very prescient to me in recent years the concept of realizing an energy within yourself, and realizing a capacity to keep on giving especially. That you actually do have so much to give. At times voices of your mind might tell you negative things: that you are “too tired” for something, that you can’t afford to help another, that you need to give up on a project or an effort. Of course, it is important to protect and support yourself above all else. But often you actually do find in your heart an almost boundless exertion, an ability to give to others or to continue on. And if it is present in your heart, you may be astounded how far your body and mind can go. Whether, for me, that be in an intense physical effort, helping others at work, or simply small kindness actions when you already feel tired or low yourself.

I am reminded of a quote from a show I have watched with close friends: “Set your heart ablaze!” If I breathe for a moment and look within, during a difficult effort, I may find that in fact my heart is ablaze, and has been the whole time. That each of us may in fact possess a tremendous inner strength, inner pool of energy and compassion, for that has indeed been our nature all along. Jake YarrisParticipant

Jake YarrisParticipantTo be honest, at this time I don’t really have a “large concern” in my life. However, I think that based on my internal patterns of personality and conflicts, the main “large concern” that I feel may arise has to do with being concerned for what I will decide to do with my future: will I find a path that is fulfilling? Will I be making enough good in the world? Will I be “successful” or will I be “wasting my time”? At times I feel conflicting forces of wanting to be traditionally successful and stable while also contending with the intensely creative and imaginative forces that are inherent within me. With the desire to give my creativity as much of my time as possible, despite a perceived lack of material gain or “success” from that time usage.

I think the truths can be very helpful in this regard. You could take many angles. You could say that grasping to some concept of “success” is not actually real, and causing suffering. You could say that grasping to my identity as being “creative (wasting time)” or “smart and successful (avoiding what calls me)” are both ideas that can cause me suffering by the grasping of them. You could say that indulging in these mental conflicts and fueling their spiral is also a vector of pulling me away from reality, causing suffering. You can look at the eightfold path, and see that actually, if I am dedicated to these goals, the “right” path will arise organically. If I am following positive karma in my actions and decisions, then benefit will arise as a result. It is possible to both 1) invest in my own creativity and 2) work to make money to support myself WITH right view, action, intention, concentration.

And in terms of worrying how I spend my time: right livelihood outlines a pretty simple definition. Making money or acquiring “success” is nowhere within those eight folds. To work with our mind, to plant seeds of compassion and benefit, all one step at a time: the teachings say, if these are our goals, the diminishment of suffering will simply arise as a result of our work. -

AuthorPosts