Art for Contemplation

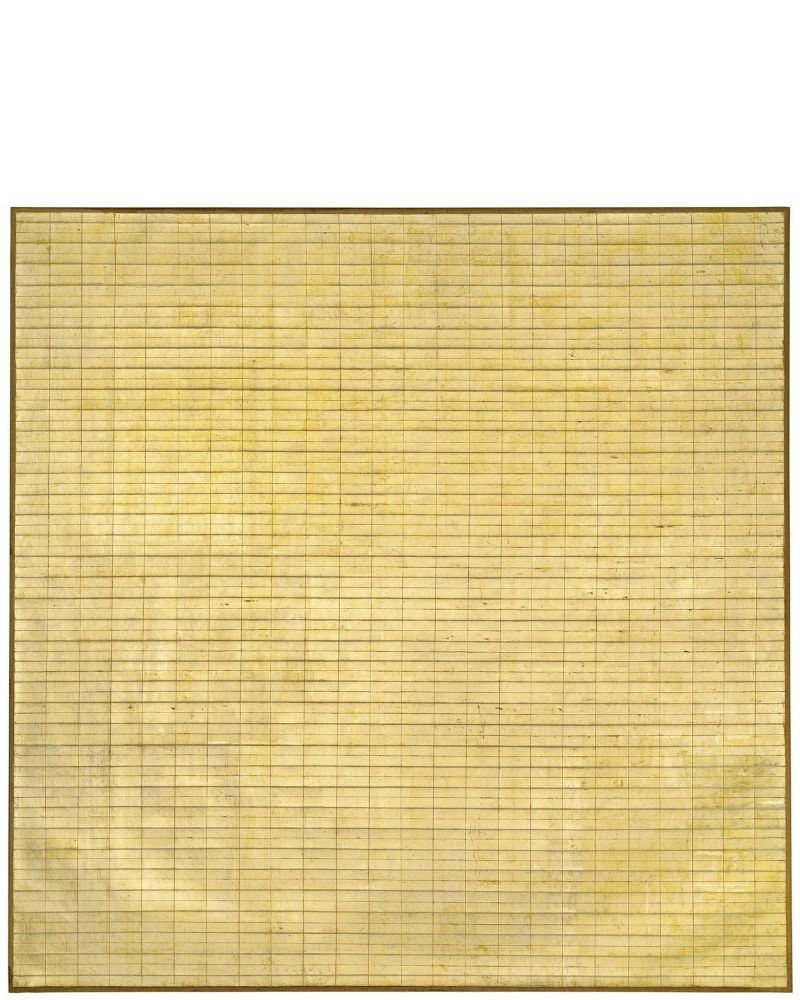

Agnes Martin, Friendship, 1963

Sitting in a little chair in her Taos, New Mexico, studio, Agnes Martin would wait and wait, sometimes for weeks on end, for inspiration to arrive. And arrive it would, as if delivered by USPS. For Agnes Martin inspiration showed up as a fully-formed mental image of a painting about the size of a postage stamp, communicating simple, elusive concepts like “Beauty,” “Hill,” “Innocence,” and so on. “I’m an empty mind,” she said. “So when something comes in you can see it.” Her only real duty was to find a way to translate that mental picture into a physical one by way of a series of complicated mathematical equations which allowed her to scale the stamp-sized image up on her 6 x 6 foot canvas.

Ironically, and unlike most other large works, you can’t really step back from a Martin painting in hopes of seeing what it is. On the contrary, they require you to step not just toward them, but into them. At such close range you find yourself holding your breath for fear that a sharp exhalation would send the mirage quivering back into the ether. Depending on your proximity to the canvas, the grid rises and falls like gooseflesh on the back of your own neck when you notice a stranger has been staring at you for a few moments too long. These paintings totter at the edge of minimalism, but are still abstract down to their canvas stretchers. These are not paintings that gratify our roving eyes’ desire for flashy entertainment or narrative, and any tatty grabs at an easy answer only inflame frustration. Martin herself often commented on the fact that in music, (which she considered the highest art form) we accept pure emotion, but from art we demand an explanation. There is no Readers’ Digest version of an Agnes Martin painting.

As she described it: “Every day for twenty years I would say, ‘What am I gonna do next?’ That’s how I ask for inspiration. I don’t have any ideas myself. I have a vacant mind. In order to do exactly what the inspiration calls for. And I don’t start to paint until after I have an inspiration. And after I have it, I make up my mind that I’m not going to interfere, not have any ideas. That’s really the trouble with art today. It seems to me the artists have the inspiration, but before they can get it on the canvas they’ve had about fifty ideas and the inspiration disappears.”

Inveighing against “ideas” and “intellect” as an approach to making and experiencing art, Martin advocated instead for what she called “true feelings.” The kind of emotion she was trying to convey in her work was akin to the feeling that might overtake you as you approached the vastness of the ocean; a spontaneous rush of energy that defies language. She wanted viewers of her work to feel improved for the looking. She wanted us to feel happy and free. It’s interesting that the form required for her to attain this freedom was a grid…not quite Cartesian, as she preferred what she considered the more inviting rectangle to the boxy, bossy square, but a grid nonetheless. And yet through the grid she achieved something Descartes never could: intimacy, warmth, and freedom.

Agnes Martin said she was thinking about the innocence of trees when the grid first appeared, which may or may not be true. Artists, like the rest of us, tend to craft some mythology around why we do the things we do (one area therapists are particularly helpful in). But one can’t help but wonder if Martin wasn’t so much abstracting trees and grass and roses to their most essence, but rather abstracting them as she herself was abstracted. To stare at an Agnes Martin painting is to fall, not into the trance of the tree or the grass or the rose, but the trance of Agnes Martin, and to accept the invitation of such a vulnerable gesture is the height of generosity.

5 Comments

Thanks for this.

Thank you for this generous invitation to engage with Agnes’ art, in a spirit of exploration. I very much look forward to your upcoming book!

Ditto! I can’t wait either!

Did Agnes Martin ever meet Picasso?

Thank you.